A Bill’s Journey

On average, only about 10% of the few thousand bills introduced each session make it through the grueling legislative process at the Hawaii State Legislature. A lot must happen for a bill to become a law, and there are deadlines that mandate by when the action must occur.

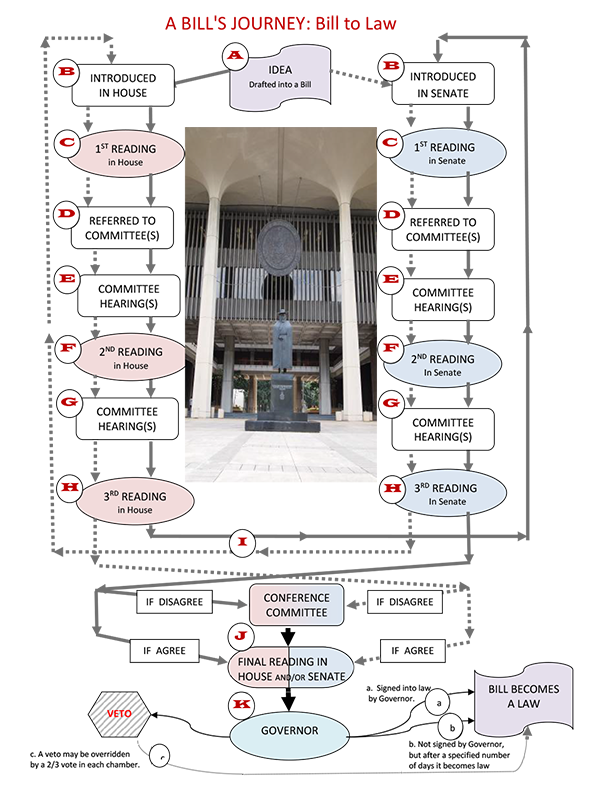

Use this diagram and follow the alphabetical notations that match the steps listed below — we’ll walk you along a bill’s path to becoming law. You may find it helpful to have the Session Calendar handy, too — you’ll find it on the Current Legislature page.

A bill may be introduced in the House of Representatives (solid line in diagram) or Senate (dashed line in diagram).

Note: Sometimes a bill gets introduced with an identical version (a ‘companion’ bill) in the other chamber. Each gets its own bill number (one an HB, the other an SB) and advances (or dies) on its own.

A

Most of the work that legislators do here at the State Capitol during the legislative session is focused on considering changes to our State’s laws. Ideas range from the creation of new laws to others seeking to amend or delete an existing law. These ideas come from a multitude of sources – legislators, state agencies, special interest groups, community groups, and constituents. To be formally considered, the idea, regardless of scope, must be introduced in the form of a bill, and bills can only be introduced by a Senator or Representative and only during the bill introduction period of each legislative session (usually the first week). Out of the thousands introduced, a few hundred of the bills will survive the legislative process and become law. Most bills will miss a legislative deadline and die. To become law, all bills must pass three votes or readings on the floor: First Reading happens at the beginning of the process, before a bill gets its referrals; Third Reading happens after a bill moves past its last committee; and Second Reading happens somewhere in between. That said, some paths are much more difficult than others – and the variable is often the number of committees a bill is referred to. It should become clear as we walk through the process.

B

A bill is introduced when it is submitted to the Chief Clerk’s Office in its originating chamber and assigned a number. The bill number (HB___ or SB___) will stay with the bill as it makes its way through both chambers. If it gets changed along the way, draft numbers are added to the bill number (HD__ or SD__).

C

After introduction, the bill will go for its First Reading (floor vote) in its chamber of origin. This is the first floor vote by the entire House or Senate, one of 3 required votes for a bill to clear a legislative chamber. From what we’ve seen, every bill passes its first vote!

D

Following First Reading, leadership in the House or Senate (depending on which chamber the bill is in) refers the bill to committees that have jurisdiction over the provisions in the bill, as determined by the rules of their chambers as well as past referral decisions. The first committee a bill is assigned to is usually referred to as its subject matter committee, the committee that has the primary jurisdiction over the bill. The subsequent committees listed usually have broader jurisdiction. [For example, a House bill concerning physical exercise with financial implications may be referred to Health (HTH), then Finance (FIN).] Each committee usually only focuses on the portion of the bill that is under its jurisdiction. For the bill to survive the process and become law, it should pass every committee it’s referred to in the order listed. This is where it can get a little tricky – some of the deadlines that may apply to a bill are based on the number of referrals a bill has. A bill with more than one referral has more deadlines attached to it. That is why referrals play such an important role in the process. (See the “Which Deadlines Apply?” handout on the Current Legislature page for help deciphering a bill’s deadlines.)

E

Once the subject matter committee receives the bill, the fate of the bill is in the Chair’s hands. If they want the bill to move forward, they’ll schedule it for a public hearing, the committee will vote to pass it, and the Chair will report it out of their committee (file the committee report and any amended version with the clerk’s office). If they don’t take any action on the bill, or don’t report it out by an applicable deadline, the bill will die in committee (this is the fate of many bills).

F

If a bill is reported out of its first committee, it goes to the floor – either for Second Reading (its second vote before the entire chamber) or merely to have its committee report accepted and to be sent on to its next committee. It’s not set in stone as to when Second Reading occurs – if a bill is changed in its first committee, it may go for Second Reading right away. If a bill is passed without changes in that first committee, it may go to the floor just in order to have its committee report adopted and to be moved to its next committee. Watch out for the First Lateral deadline: deadline for the bill to move into its last committee.

G

Subsequent committees must schedule the bill for a hearing or decision making, pass the bill, and report it out before the next applicable deadlines. Watch out for the First Decking deadline: deadline for the bill to move out of its last committee and be scheduled for the Third Reading vote.

H

Then it’s back to the floor for Third Reading on the bill, the last of the three required votes for the bill to move through the chamber. If the bill has changed at all since the last time the chamber had the bill, the new draft of the bill must be made available to members at least 48 hours before taking the third floor vote. It must pass that vote by the First Crossover deadline.

I

A bill that survives the process in its originating chamber (is voted on 3 times and moves through all the committees it’s been referred to) will cross over to the other chamber and go through the process again. Repeat steps C through H, only in the non-originating chamber this time. Note that the deadlines for the bills in their non-originating chamber are labeled as “Second,” i.e., Second Lateral, Second Decking, and Second Crossover (as opposed to First Lateral, First Decking, and First Crossover in the originating chamber).

J

A bill that passes the non-originating chamber without changes goes back to its chamber of origin and is transmitted from there to the Governor. (NOTE: While bills proposing changes to the Constitution of the State of Hawaii go through a similar process, instead of going off to the Governor, they are put on the ballot for the voters to decide on whether they should become law.) If a bill is amended by the non-originating chamber, it goes back to the originating chamber where that chamber will have an opportunity to either approve of the amendments (and vote on the changed bill and send it on to the Governor) or disagree with the changes (this is the usual path). If they choose to disagree, the House and Senate can try to reconcile their differences via conference committees. For each bill reaching this point, the House and Senate leadership select members to serve on committees to meet and resolve disagreements between each chamber’s version of the bill. (Usually, the subject matter chairs will be assigned as Conference Committee Chairs to take the lead in discussions to find a compromise.) Rules governing the conference process are agreed upon and published each year. They must end their deliberations and reach agreement by the Final Decking deadlines. [There are two final decking deadlines – one for fiscal bills, the other for non-fiscal bills. If a bill received a referral to Ways and Means (WAM) or Finance (FIN), the fiscal deadline applies.] If the conferees do reach an agreement on the final version of the bill, they will publish a Conference Draft of the bill which goes before the full House and Senate for one last vote. That vote must take place before the end of session – adjournment sine die.

K

The Governor has constitutionally mandated deadlines to act on bills transmitted by the Legislature. If the Governor signs the bill it becomes law. If the Governor vetoes the bill the Legislature can override the Governor’s veto by 2/3 vote in each chamber by a specified time. If the Governor neither signs nor vetoes the bill by a certain date, the bill becomes law without signature. (Note: To find out when a law takes effect, look at the end of the bill for its effective date.) Enacted bills become Acts of law and are given an act number. Permanent laws end up in the Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS). All bills, including those that do not have permanent provisions, end up in the Session Laws.

Biennium

While we talk of bills dying during session, in the first year of the two-year biennium, the bills actually carry over to the second year when they can again be acted upon. They can be revived from right where they were at the close of the first year’s session – in other words, they don’t lose the progress they’ve made. (For example, if they already survived First Lateral, they won’t have to worry about that deadline the next year – they’ll just have to focus on making the First Decking deadline.) At the end of the second year, all bills that haven’t passed out of the legislature are dead. We then have new elections, and a brand-new biennium starts up in the odd-numbered year.

Looking for a simpler outline of a bill’s journey? Give us a call and we’ll walk you through it.